Determining the ideal counter-damage number - part 2

Finding the "sweet" spot

In part 1 of this topic, we introduced the challenge that the defense faces in addressing the topic of damages and counter-damages. In part 2 we explore how to test and validate the impact of counter-damages.

Methods Matter: Ensuring the Validity of Online Tests of Counter-Damages

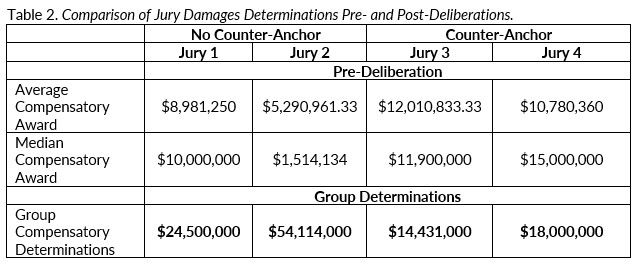

To accurately evaluate the impact of counter-damages numbers, the research must include deliberations. Having each mock juror provide an individual damages determination and then averaging, or taking the median, of those individual awards, can be significantly different from the group determinations. For example, in Table 2, additional data from the same experimental mock trial shown in Table 1 are revealed. As shown in Table 2, the average and median juror awards prior to deliberations were lower in the groups that heard no counter-anchor, compared to groups that heard a counter-anchor. If this research had been performed without having the jurors deliberate, the defense may have mistakenly believed that it was better not to provide a counter-damage number. However, it is common for jurors’ verdict leanings to change after they deliberate, and in some cases, as in the one shown here, there is a shift in favor of the plaintiff that occurred across all groups. The tendency of a group to arrive at a more extreme decision than any one of the individuals in the group would have arrived at individually has been known to psychologists for decades and is referred to as group polarization or “risky shift”[i]. The fact that all four groups in the example experimental mock trial arrived at determinations of damages that were greater than the group averages indicates that the actual trial jury would likely do the same. As jurors discussed the case, the plaintiff’s arguments were more persuasive than those of the defense, and jurors across groups adjusted their damages upward. The factor that kept the damages from becoming more extreme for juries 3 and 4 was the counter-damage number provided by the defense. In this case, it was clear that a counter-anchor would be a useful strategy in court.

Identifying the Ideal Counter-Anchor

Most commonly, the cases headed to trial are ones that would benefit from a defense counter-anchor, and the question is not whether to provide a counter-anchor, but what amount is ideal to suggest. Again, an online mock trial methodology is ideal for this test. One panel of mock jurors is exposed to one counter-damage number and a separate, matched sample, is provided a different number. Typically, one panel is given a very low counter-damage number and the other panel is provided a number a little higher. At times, the results reveal that both panels were at too low of a number. In this case, a new panel can be recruited and exposed to the same presentation with a slightly higher counter-damage number and the process is repeated as many times as needed.

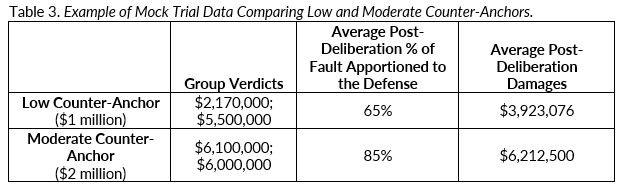

Table

3 is an example of data obtained from an online jury research experiment

designed to test the impact of different counter-anchors. The case evaluated

was a trucking accident in which the plaintiff requested $6 million. The

defense admitted to having some liability, but also contended the plaintiff had

a percentage of liability as well. As shown in the table, providing a low

counter-anchor of $1 million resulted in lower group verdicts compared to the

counter-anchor of $2 million. Additionally, when provided a lower

counter-anchor, jurors individually apportioned less fault to the defense and individually

determined less damages at the conclusion of the deliberations. These data indicated that a counter-anchor of

$1 million was clearly effective for the defense. In this case, a second test

to determine whether a counter-anchor of $500,000 or $750,000 would be just as

effective, or even more so, revealed that the “sweet spot” was $1 million given

jurors tended to react negatively to a defense number they found to be too low,

which was anything lower than $1 million for this case.

Commonly Held Concerns Regarding Counter-Anchors

A common concern of defense counsel and insurers is that if a counter-anchor is provided, then jurors will simply split the difference and award an amount that is half-way between the plaintiff ad damnum and the defense counter-anchor. At times, it is true that jurors will use this method of determining damages. Importantly, though, this method may result in a better outcome for the defense when compared to not offering a counter-damage number at all. The only way to know for sure is to test the case using mock trial methodology.

Another common concern is that if the defense provides a counter-damage number then jurors will assume the defense acknowledges fault and will perceive the counter-anchor to be an “offer.” If the defense has a very strong case and a good chance of a defense verdict, it may be possible that providing a counter-anchor could work against the defense. However, in our experience most cases that are headed to trial are not so imbalanced in favor of the defense. We have seen attorneys uncomfortably provide a counter-anchor in a mock trial, seeming to doubt themselves as they speak, and still reach the outcome of lower damage numbers compared to the test in which they provide no counter-anchor. With practice, an attorney can deliver this message confidently and clearly, which is even more likely to have the intended effect of reducing the damages.

At the same time, we recognize that there are often jurors who do misunderstand the rationale for the defense providing a counter-damage number. It is common to hear at least one juror state, “Well, if the defense did not believe they had any fault, they would not have offered the $500,000.” Importantly, though, even when jurors misunderstand the defense’s rationale for countering the damages, the number still works to reduce the damages. Thus, it is often ideal to provide a counter-anchor, though it is best to test each case to determine scientifically what is the ideal strategy to employ.

Conclusion

Plaintiff attorneys are sharing winning strategies and teaching the less experienced in their field how to aim high in their demand as well as the ad damnum in court. With the media reporting only the highest verdicts and attorney advertisements boasting of large wins on YouTube, blogs, billboards, radio, social media and park benches, the defense has an uphill battle by the time they reach the courtroom. Rather than wait for trial and try to determine how to combat the plaintiff’s anchor, defense teams need to be proactive and test their case and their trial strategies well ahead of the trial date. By scientifically determining the effect of suggesting a counter-anchor, or the effect of different counter-anchor sizes, the defense will enter the courtroom armed with a tested and proven game plan.

[i] Myers, D. G., & Lamm, H. (1976). The group polarization phenomenon. Psychological Bulletin, 83(4), 602-627.